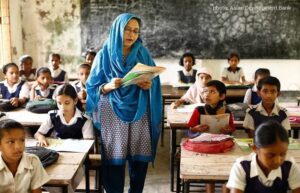

How to address the global teacher shortage?

At the start of the school year in many countries, the media are reporting a shortage of teachers, with the most dedicated and passionate educators growing tired of the lack of support, resources and recognition for them. A new report examines trends in the teaching profession around the world and makes recommendations to improve the situation.

According to the latest calculations by the International Task Force on Teachers for Education 2030 and UNESCO, released on World Teachers’ Day, recent data shows that sub-Saharan Africa alone is expected to recruit 16, 5 million more teachers to meet education goals by 2030.

This means that 5.4 million new teachers are needed at primary level and 11.1 million at secondary level, to meet the needs of the region’s growing school-age population and limit the growing number of out-of-school children. .

Countries in the Sahel region, especially countries like Niger and Chad, are in a particularly critical situation and need to double their number of primary school teachers to achieve these goals.

In South Asia, despite progress in some countries, there is still a substantial deficit of 7 million teachers: 1.7 million teachers will be needed in primary education and 5.3 million in secondary education. However, this is a considerable reduction from previous projections.

The low projection for primary school teachers can be attributed to progress in universal primary education in Bangladesh and India, as well as declining birth rates.

Elsewhere in the region, in Afghanistan and Pakistan for example, the annual growth rate of primary teachers would need to increase by around 50% or more than 10% per year to achieve universal primary education by 2030.

Teacher shortages are not unique to the developing world. They also affect countries like Australia, China, Estonia, United States, France, Great Britain, Japan, Malaysia, Netherlands and many others.

COVID-19 has only exacerbated the current teacher recruitment crisis

The COVID-19 pandemic is partly responsible for this problem: their fragile health and the stress linked to the pandemic have caused many teachers to resign. However, we know that COVID-19 was only the tipping point and only worsened an already problematic situation before the pandemic.

A Guardian article reports that 44% of teachers in England plan to quit in the next five years, with most blaming their heavy workload. A survey of 8,600 teachers in New South Wales, Australia also found that more than half of teachers surveyed were planning to leave the profession within the next five years.

Teacher attrition has many causes, including lack of financial incentives, poor working conditions, high workloads, lack of preparation, low autonomy, inadequate administrative support, poorly designed classrooms and a lack of teaching resources.

Emigration in search of better opportunities is also a cause of attrition. In France, a recent study found that in the 1980s, a beginning teacher earned 2.3 times the minimum wage. Today, that equates to just 1.2 times the minimum wage.

In underserved areas and crisis contexts, already difficult teaching conditions are compounded by a lack of qualifications and professional development opportunities for teachers; and by inequitable methods of deployment that involve placing the least qualified and least experienced teachers in areas where the best are needed.